Since 2014, the Coastal Federation has partnered with the NOAA Marine Debris Program, N.C. Sea Grant, N.C. Marine Patrol and local commercial fishermen to remove derelict fishing gear from northeastern North Carolina waters.

This year marks our third year of data collection. Approximately a dozen commercial boats dispersed throughout the entirety of the Marine Patrol’s Northern District 1 (D-1), spanning from the Virginia line to Ocracoke. Fishermen were paid per day of work and guaranteed three days of work – as the weather allowed. Each boat was equipped with its own side-scan sonar and electronic tablet for data collection. The charge was simple: search and find efforts for both ghost (no buoy visible) and visible crab pots (buoy visible).

So, why do this project… and why pay fishermen?

- The hired commercial fishermen are on the water every day. Through their daily commute and fishery, they are able to visualize where these pots are accumulating over the course of a year. Pots can become “derelict” in a variety of different ways: they can be significantly moved as a result of large weather events; in some cases, we have seen pots move nearly 10 miles as a result of one storm. Pots can become hung in man-made structures (i.e., bridges), or pots can drift into vessel channels over time, increasing the likelihood of buoy detachment by vessel traffic. Employing fishermen to clean up pots is a simple solution: if you understand the movement of the water, you understand where the pots will end up.

- January is generally a slower month for crabbing and fishing, and therefore a good period to offer an economic incentive for a positive, consensus-building activity. This project is based on bringing many groups together: commercial fishermen, nonprofits, scientists, law enforcement agents, etc. We’ve all got the same interest in mind, so let’s get the sounds clean during the one window of time that we can.

- This project is saving the state money. It is estimated that over the past three years, Marine Patrol’s resources used during the cleanup (staff time, boat operation, travel, etc.) have been reduced by at least half as a result of this effort.

It’s important to note the timing of this project. From Jan. 15 – Feb. 7 each year, commercial fishermen are required to have crab pots out of the water. Therefore, anything left behind during this period is considered derelict and is legally able to be collected. N.C. Marine Patrol has led these efforts since 2003. While Marine Patrol still plays a large role in the cleanup, select commercial fishermen are now directly responsible for removing the pots.

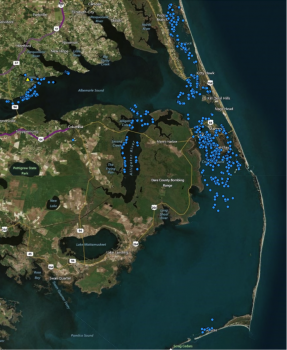

In total, 753 pots were collected this year: 54 by Marine Patrol, and 699 by commercial fishermen (see Figure 1). These results were achieved by focusing on areas where pots are known to accumulate, based upon the past year’s weather events and crabbing patterns (i.e., where pots were set).

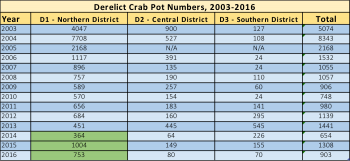

Over time, we’ve found that a couple external factors dictate that number of pots that are collected each year. Significant weather events and the fluctuation of pot prices tend to have the greatest impact on the number of pots that become lost each year (see Figure 2). When the cleanup began, the numbers of pots recovered during the closed period were insurmountably higher than what we are finding now.

It is believed that significant weather events (i.e., hurricanes) and low pot prices during these years resulted in the higher yields. It is assumed that a lower pot price means less incentive for fishermen to voluntarily search for lost pots. Over the years, the cost of a crab pot has grown to about $45 per pot. This rise in price has attributed to fewer pots now being found. Plus, years without a major hurricane during peak crabbing season has shown to also influence the number of pots being retrieved.

Figure 2. Derelict crab pots collected from 2003 – 2016. Cells highlighted in green denote where commercial fishermen were hired to complete the cleanup, only in District 1 (D1).

In the past, data on pot location and bycatch was recorded by hand on paper datasheets. While effective, this method proved to be quite time consuming in freezing temperatures and gusty winds.

This year’s cleanup boasted some new technology that improved the process. N.C. Sea Grant’s, Sara Mirabilio and Gloria Putnam offered to test this new method for us last year. Putnam was able to create a specialized application for our purposes using CyberTracker, a free data collection software for smartphones and PDAs created by a South African nonprofit. CyberTracker began in the Kalahari Desert, where the imperiled hunter-gatherer lifestyle was given new meaning through technology. The program is used all over the world and is available for free – all in the name of environmental monitoring on a global scale.

With additional funding from the NOAA Marine Debris Program for 2016 and 2017, the project was able to purchase electronic tablets to run this new data collection application. The resulting ease in both data collection and analysis has saved untold hours of data entry and map-making.

Just like any smartphone or tablet these days, the camera is part of the package. As such, the fishermen were able to take pictures in the electronic datasheet with little trouble. The photographs collected on the tablets serve to better explain the data, as well as to illustrate the additional human element of this work.

Stay tuned for the project’s progression at the Coastal Federation’s website.