Our native eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) is one of the most important species in our estuaries. Oysters benefit North Carolina’s coastal ecology and economy. They filter water, provide food for humans, and create reefs that build homes for more fish. These environmental benefits, in turn, support jobs and provide economic opportunities for coastal communities.

The Coastal Federation is working to restore wild oyster populations by recycling oyster shells and putting those shells back into the water. It’s a critical step in ensuring that North Carolina’s coastal ecology and economy continue to thrive. Shell recycling partners are a crucial part of the Federation’s recycling efforts, and there are several resources available to help support shell recycling.

Toolkit Resources:

Adopt An Oyster

Another way you can help is by adopting an oyster. Whether you adopt an individual or a bushel, that support directly benefits all of our oyster restoration work. Throughout the Federation’s restoration season, the donor will receive four updates about the oyster’s experience, from the recycled shell to a young adult beginning to filter water.

Did You Know?

“Every dollar invested in oyster restoration provides at least $4.05 in benefits, such as increased economic activity through recreational activities and tourism, with jobs in fishing and restoration, and even in local seafood sales.”

The Pew Charitable Trusts Research

The 3 F’s! Oysters provide us with food, fish habitat, and filtered water.

Instead of using hardened structures like bulkheads, building living shorelines using recycled oyster shells stabilizes the banks, helping to control erosion while providing habitat, absorbing stormwater runoff, and promoting clean water through the growth of new oysters.

Oysters can help protect our coast from storm surge and damage from hurricanes. This natural infrastructure can increase our resilience to storms by strengthening and reinforcing our shorelines.

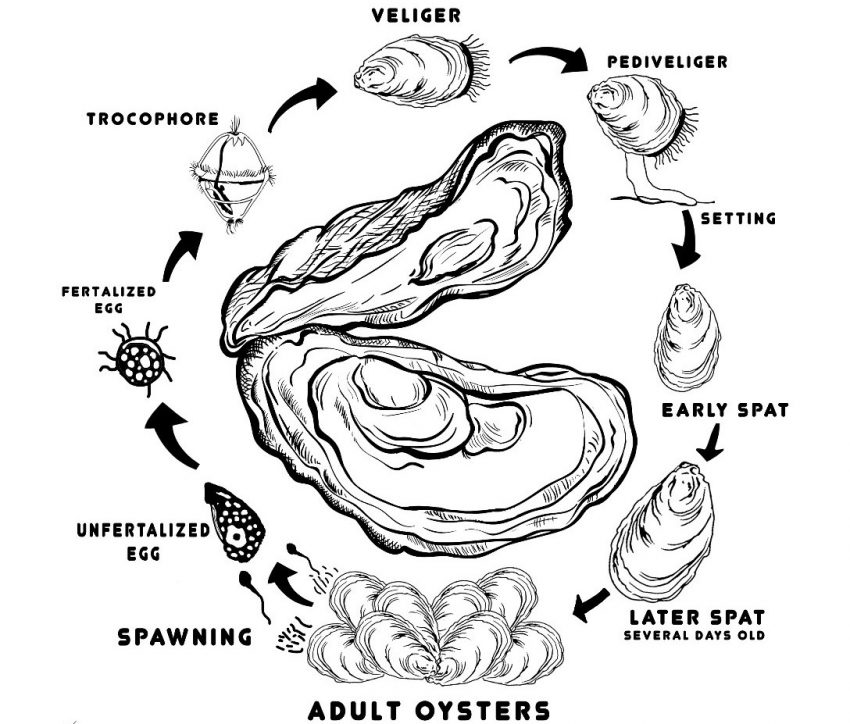

The Life Cycle of an Oyster

Adult oysters start out on the reef. When they receive a signal (which could be environmental—salinity, temperature, light, and/or a chemical cue or all of the above) the males release their sperm into the water, which signals for the females to release their eggs. This is called broadcast spawning, when they simply release the eggs and sperm into the water.

The sperm and egg find each other in the water, and the sperm fertilize the eggs. Then the baby oyster (or larvae) floats in the water for about two weeks. This is the only time in the oyster’s life that it is not attached to a reef. We say that the oyster is free swimming, but it can’t really control where it goes, it’s at the mercy of the currents.

The baby oyster goes through a few stages of metamorphosis while they are in this free-swimming era of their lives. At one of the later stages of their development (scientifically known as the pediveliger stage), they develop an “eye,” which can detect light v. dark (but can’t see the same way we do), and a “foot,” which helps them find a hard surface to land on.

Once they find a hard surface to land on (hopefully it’s on an oyster reef with other oysters around, but it could also be a piece of rock, marl, piling, a crab pot, or something else entirely—collectively referred to as cultch), the foot sticks the baby oyster to that surface. Then they start to grow into an oyster like we would know it to be.

As the oysters grow, they filter plankton from the water for food. They are also able to take calcium carbonate out of the water and use it to grow their own new shell.

They grow two shells—a left and right valve and never move from their reef again *unless they are harvested or transplanted. Once the oyster reaches maturity, in about a year, it will start the process over again—releasing sperm or eggs into the water that fertilize each other and create new oysters.

Fun Facts

Most oysters start out as males and as they mature, they become female.

Oysters can switch back and forth between males and females if environmental cues tell them they should.

Oysters can spawn more than once in a year but typically do so when waters start to warm up in the spring.

Recycled oyster shell makes a great surface for new baby oysters to land on.

In North Carolina, we say we are lucky in that we still have plenty of baby oysters floating around in our sounds, and if we put clean, recycled oyster shell, and other suitable materials in the water, we can catch the baby oysters and grow new reefs. The Federation likes to say: if you build it, they will come. If we put the reef material in the right place at the right time, the baby oysters will find it and grow into a new reef. In some states, they have to put cultch material in the water, grow the baby oysters in a lab and release them on the reefs.